Buildings are repositories of memories. When they withstand the ravages of time, their hallways and walls tell many stories. The Luneta Hotel is one such building. It rose during the most hopeful period in Philippine history, witnessed Manila's golden age, endured a world war, yielded to sin and decay, fell into obscurity, and then rose again to its former glory.

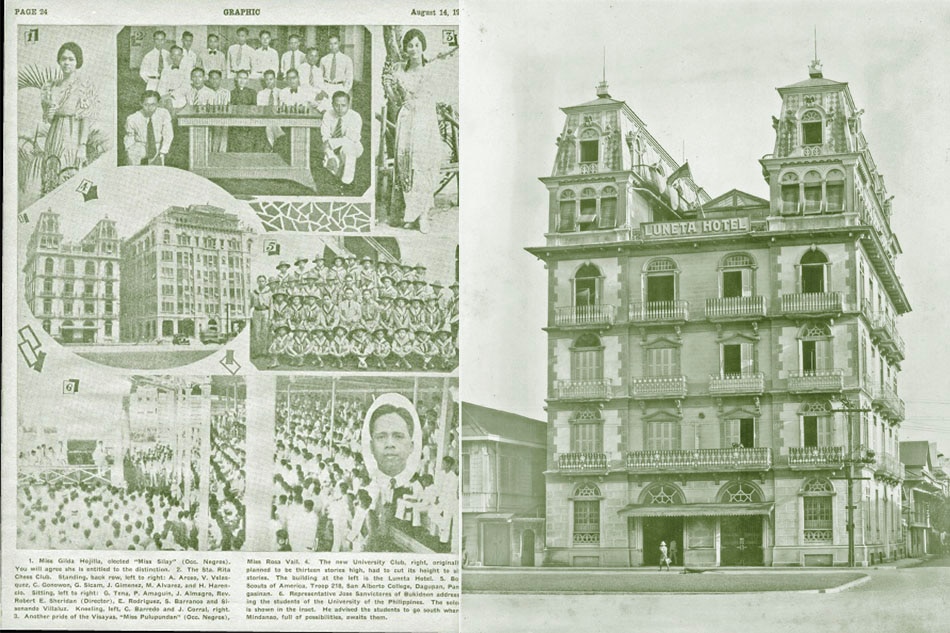

When it was built in 1919, the Luneta Hotel was the highest structure in its vicinity, all six stories of it. It towered over rows of bahay na bato and bodega in the elite district of Ermita. Designed in French Renaissance Belle Epoque style by the Spanish architect-engineer Salvador Farre, it rose on the corner of San Luis (now T.M. Kalaw) and Alhambra Streets.

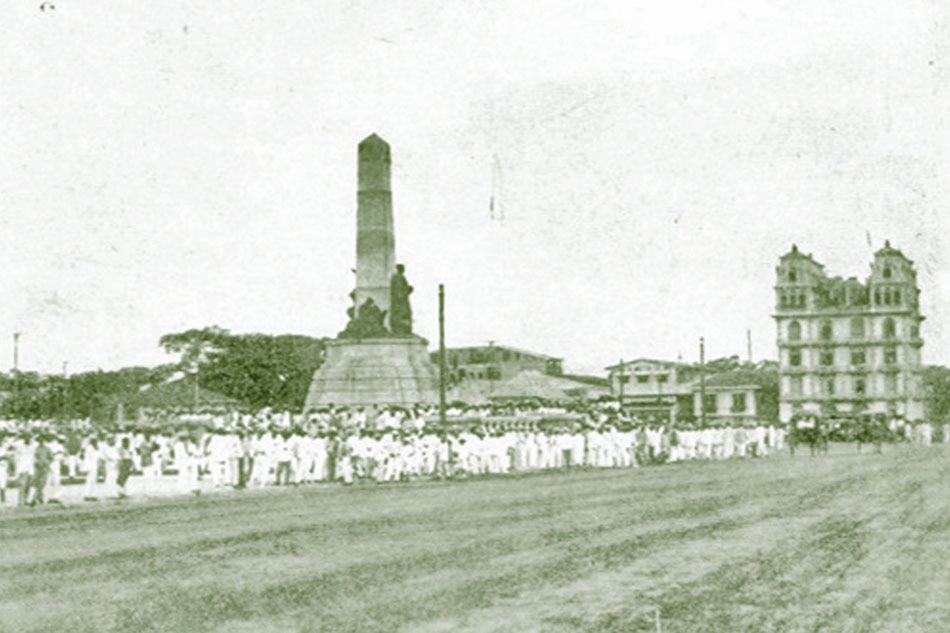

The hotel, which was built with reinforced concrete, faces Luneta Park with a direct view of the Rizal Monument. It was one of the earliest luxury hotels to populate the "new" Luneta Park area, to complete American architect Daniel H. Burnham's vision for Manila.

There were many other structures of note during that time—the art nouveau Uy-chaco building, the neo-classical architecture of the Insular Ice Plant and Cold Storage, The Manila Hotel, and The Army-Navy Club. But the Luneta Hotel was the only one of its kind done in Belle Epoque style.

Handsome and quietly elegant, its grilled balconies were of cast iron, said to have once shimmered like diamonds and rubies in the sunlight. Its French-style mansard roof were reminiscent of the rooftops along Boulevard Haussmann and parts of the Louvre in Paris, while the dormer windows were once punctuated by iron finials and cresting. The concrete gargoyles were fashioned like crocodiles, lions, griffins, and alligators, and functioned as intended: spewing rainwater from the gutter system away from the building.

Originally, it had 60 rooms, each with its own private bath, and two suites with amenities that included telephones in every room. The hotel also had a restaurant and coffee shop.

Like the Manila Hotel across the road, the Luneta Hotel had the gravitas of similarly designed French Renaissance Revival structures like Hotel de Ville (1880) and Hotel Lancaster in Paris (1889), the chateauesque mansions on New York's Fifth Avenue like the William K. Vanderbilt mansion (1878), the Fletcher-Sinclair mansion (1899), the Warburg mansion (1908, now the Jewish Museum), the Morton F. Plant mansion which is better known as the Cartier Building (1905), and the original site of the Waldorf-Astoria (built in 1893 but closed in 1929 to make way for the Empire State Building).

Luneta Hotel was a reflection of the time's hopeful spirit: out of the shackles of Spanish rule and on the verge of promised changes from the Americans. Its elegance matched its habitués: dignitaries and the social set.

In the beginning, the hotel was run by its proprietor L. Burchfield and general manager F.M. Lozano. It was frequented by merchant marine officers and sailors due to its proximity to Manila Harbor. It gained international renown when it hosted the delegates of the 33rd International Eucharistic Congress at Luneta Park, the first of the series to be held in Asia, opening what Time magazine called the Catholic Church's "Oriental Pearl" to the world.

During the Second World War, Luneta Hotel became the home of American non-commissioned officers. Its grandeur gave way to decadence. It also became a base for retreating Japanese war soldiers who defiled the hotel. Though it was one of the few buildings that survived the Liberation of Manila in 1945, it was not the same.

In 1952, the hotel was bought by an entity referred on record as Lednicky, who later sold it to Toribio Teodoro, the owner and proprietor of Ang Tibay shoes. During the Marcos era, ownership was transferred to the Panlilios.

The post-war years saw Luneta Hotel struggle to remain Manila's premiere hotel. Angelo Farinas, an architecture graduate and consultant at the hotel, said Imelda Marcos once occupied the fourth floor. A few oldtimers had told him how they would dine at the hotel after a night at the cinema.

In 1984, it was used in the Chuck Norris movie Missing in Action, with the hotel's facade and interiors made to look like a part of Hanoi. Some might even remember the hotel's famous The Third Eye disco, located in the basement where, decades earlier, American soldiers used to store their ammunition.

The hotel fell into disrepair shortly after. In spite of renovations during the 1970s and the 1980s, it prevailed only on the strength of Presidential Decree 1505, enacted in 1978, prohibiting the alteration of historic edifices without the prior written permission of the National Historical Institute.

In 2007, a private heritage group approached the late Cipriano Lacson of Malabon and persuaded him to restore the hotel to its old glory. The well-traveled Lacson was an advocate of the arts. His granddaughter Nina Lacson, who flew in just for the hotel's formal opening, recalls how he once had a map in his office with pins on every single country he had been to, with France being his favorite. In fact, Paris was the last city he wanted to go to, and the last city he had seen, before he passed away in 2011.

"When they came to see him [about acquiring the hotel], he said, 'Yes, absolutely,'" Nina recalls of her grandfather. "He's a very generous man and this is his way of giving back to the community," she adds, citing the history, culture, and Filipino pride her grandfather wanted to foster.

The renovations of the Luneta Hotel began in 2008. That was when speculation ran rampant about its fate: has it changed hands? Will it be demolished? Who was behind Beaumont Holdings which signed the business permit for renovation?

The following year, the Cultural Heritage Act of 2009 (RA 10066), which preserves buildings over 50 years old, was enacted. The law came in the wake of the demolition of the Jai Alai building on Taft Avenue, one of the best examples of the Streamline Moderne style of the 1940s, the era in which it was built. The law ensured the Luneta Hotel would remain standing.

Consequently, the hotel was renovated according to the standards of heritage boutique hotels all over the world, with concessions to structural soundness. A staircase on the ground floor was introduced with an elevator core servicing all six floors. The staircase was partly fashioned from 400-year-old wood donated by the San Bartolome Church, the late owner's parish in Malabon. The wrought iron grills that once served as windows and gates have been repurposed as accents in Café Yano on the ground floor. The Salvatorre Lounge on the sixth floor used wall tiles from the original structure. Even the gargoyles were retrofitted so they no longer function as downspouts.

The effect, say those who have stayed in the hotel in the past and have seen the changes, is still breathtaking. There is an old world charm to the act of walking to the railing of the upstairs balcony, to take in the uninterrupted view of the park and the bay. On the opposite side, what you see from the sixth floor balcony is reminiscent of the kind of view from the rear of quaint Parisian apartments.

It took a long time for Luneta Hotel to regain the gleam of its filigreed rails, but the process has come to rest.

Photographs by Jar Concengco

Archival images courtesy of Lopez Museum

This story first appeared in Vault Magazine Issue 17 2014.