One of the greatest gifts a father could give his son is to set him on a path to becoming his best self. The revered Filipino statesman and nationalist Jose W. Diokno, who would have turned 100 years old this February 26, did just that to his eighth child, Jose Manuel Tadeo "Chel" Icasiano Diokno, a few months after the boy turned 13 years old.

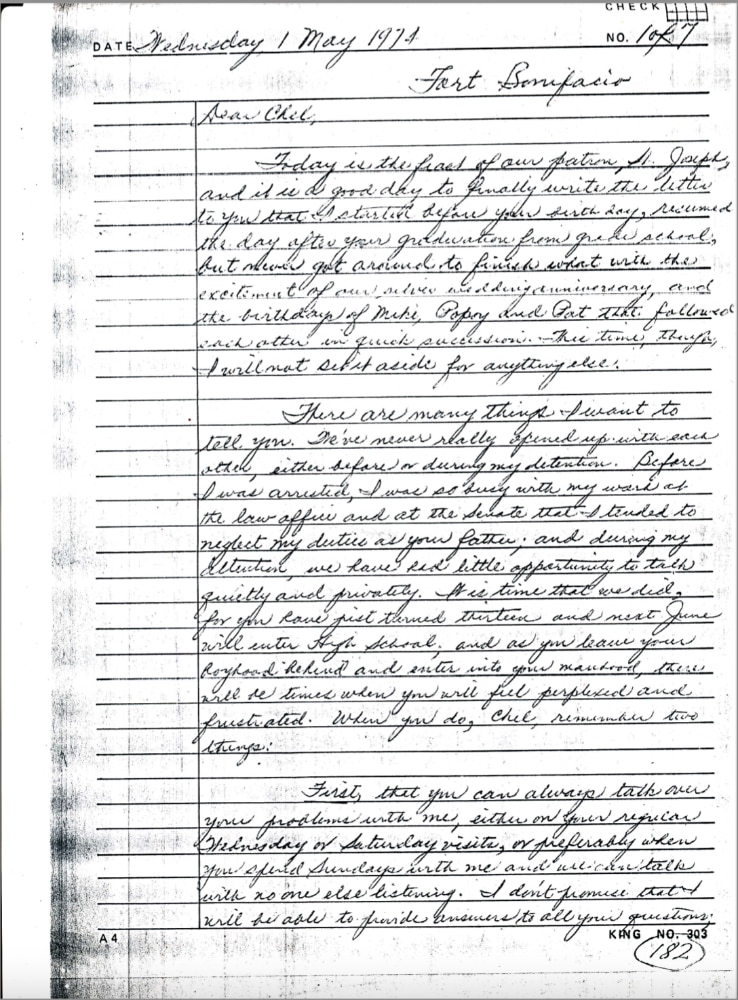

The young Chel received an inspiring and moving letter from his father in May 1974, one filled with affection and pride, as well as wisdom to arm him for the future. The older Diokno, or Ka Pepe as he was known to many, was then on his second year in incarceration at Fort Bonifacio, and there was no telling what the future looked like. While Chel and the rest of the family were allowed to visit the Senator, father and son rarely got the chance to chat privately. This is perhaps why he set aside time to write his thoughts for his son who was then about to begin a new stage in his young life.

“It’s a letter I treasure up to now and every time I read it it makes me realize something different about life,” Chel Diokno tells ANCX via Zoom.

The current senatorial candidate’s family shared a copy of the letter to us in pdf form as the Dioknos commemorate Ka Pepe’s centennial year. When asked if he revisits the letter once in a while, he says he does look back at it from time to time, and sometimes it brings back memories that lead to tears.

The seven-page letter, a small portion of which surfaced on Twitter October last year, provides a glimpse of what Diokno the Father was like and how he raised his children—speaking to them like they were adults, laying down their options for the road ahead, trusting they will choose the right path. It’s not your usual “choose between being a lawyer or doctor” dilemma he brings to the table—he asks the more vital “What does life mean to you?”

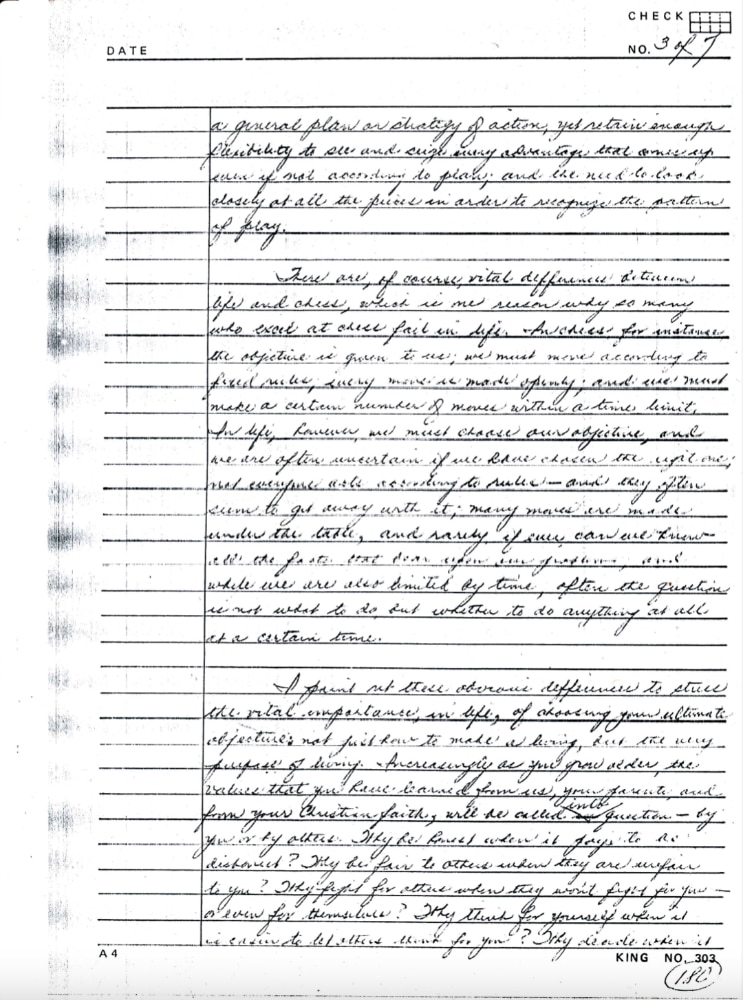

“Increasingly as you grow older, the values that you have learned from us, your parents, and from your Christian faith will be called into question—by you or by others,” writes the Senator. “Why be honest when it pays to be dishonest? Why be fair to others when they are unfair to you? Why fight for others when they won’t fight for you—or even for themselves? Why think for yourself when it is so much easier to let others think for you? Why decide when it’s less troublesome to obey? Why be good when it seems so much more pleasant to be bad?"

"The answer I think is in what life means to you. If life means having a good time, money, fame, power, security, then you don’t need principles; all you need is techniques. In fact, it’s better not to have principles: they would only get in your way. On the other hand, if life means more than those things, if happiness counts more than a good time, developing your talents more than developing wealth, respect more than fame, right more than power, and peace of soul more than security; if death doesn’t end life but transforms it, then you must be true to yourself and to your God, and to love and truth, good and beauty, and justice and freedom that are His other names and that He has made part of our human nature."

One might say it’s a lot for a new teenager to take in, and Atty. Chel himself admits “I’m sure when I was 13 I didn’t fully grasp everything he wrote there.” But the younger Diokno was also quite a bright, admirable kid, a source of fulfillment for his dad.

“I want to tell you that I am very proud of you,” Ka Pepe tells his son, “of how generally well-behaved and courteous you are; of how you stand up for (unclear) and for what you think is right and fair; of how you have disciplined yourself into losing weight and mastering the sports and games you like, like basketball and chess, while at the same time maintaining the (unclear) section of your grade—in short, of how you have maintained your values without becoming sanctimonious, and gotten along with friends of your age without acquiring the vices of the day.”

What was Senator Diokno like as a father? “He was awesome,” says Atty. Chel. “He was really a loving person. Of course, in his generation it was hard for men to really show emotion especially to the sons. But we all knew, all of us brothers knew, he loved us very much. He was very charming. He had a great sense of humor. The times I treasure the most were before Martial Law, especially the summers when he would take us down to Batangas. And we would spend weeks in the beach. And that’s also the time we’d get to spend more time with him, although he wouldn’t be with us all the time kasi kahit nandun kami sa beach minsan meron dumadalaw sa kanya, or he would have to attend to his duties as a lawyer or as a public servant.”

It’s a testament to the older Diokno’s wisdom and sensitivity that he paid special attention to his teenage boy’s mental and emotional well-being at that time. He’d already started writing the letter much earlier but certain family occasions distracted him. During that day in May 1974, however, on the feast of St. Joseph, he made sure to complete it. St. Joseph is an important saint in the Diokno household, that’s why all of Ka Pepe’s boys had Jose in their names.

Ka Pepe writes: “As you leave your boyhood behind and enter into your manhood, there will be times when you will feel perplexed and frustrated. When you do, Chel, remember two things: First, that you can always talk over your problems with me, either on your regular Wednesday or Saturday visits, or preferably when you spend Sundays with me and we can talk when no one is listening. I don’t promise that I will be able to provide answers to all your questions, but I do promise that I will listen with attention and with love…

“Second, if because of the urgency of the problem or for any other reason, you feel you must act without talking it over with me or anyone else, think the matter through first and act. Do not be afraid of making a mistake—we all do. The point is not to make the same mistake twice and to be ready to admit your mistake when you have made it and to remedy it as fast as possible and as soon as it becomes evident you are wrong.”

The Senator’s concern was perfectly understandable. Not only was Chel then in an impressionable age, he would also somehow witness his father’s suffering when Martial Law happened. The Senator strongly opposed the Marcos dictatorship, and Chel was present when his father was picked up by military men from their home. “I will never forget that night,” says Atty. Chel who was 11 at that time. “It was really traumatic for all of us.”

Visiting his father in jail would not be less scarring for the young boy. “I remember the details of our visit and how we had to suffer the indignity of being stripped naked every time we entered the detention facility,” recalls Atty Chel. “We would be searched. They had to check everything, even the food we would bring kasi daw baka may nakatago doon na sulat o kung ano man.”

One particularly painful visit was with his mother in Laur, Nueva Ecija. Senator Diokno, along with Ninoy Aquino, was moved there from Fort Bonifacio without his family being informed. He was in solitary confinement for weeks. During their visit, and after several hours of traveling, they were only given 30 minutes with Ka Pepe. “We could not even touch because there were two layers of barbed wire between us and him,” recalls Atty Chel. Curiously, Ka Pepe was holding his trousers when he met his visitors. It turns out his guards have taken his belt away, and he lost so much weight that if his hands let go of his pants they would have fallen.

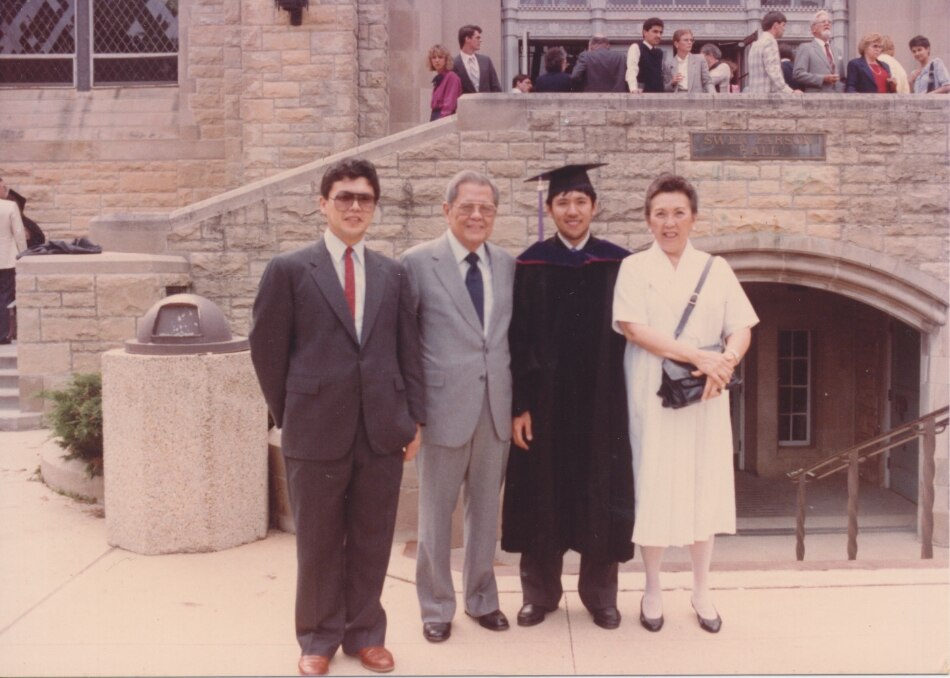

Senator Diokno was released from prison in September 1974. He passed away in 1987, the year after Edsa People Power kicked out the Marcoses from Malacañang. Chel was then 26 years old and had just passed the bar in the US where he planned to practice law for a few years. But Ka Pepe had been very sick so the younger Diokno decided to come home to the Philippines. Before this, the Senator would send Chel letters, asking him to buy some books for him. “Until his death, my dad was really a lover of books and of knowledge,” recalls the senatorial aspirant.

Atty. Chel is now 62 and has no doubt made his dad even prouder with his achievements over the years. Like the late Senator, he became an accomplished lawyer, a champion of human rights, and an educator. He is founding dean of the De La Salle University College of Law and is current chair of the Free Legal Assistance Group (FLAG) which was founded by his father.

Once in a while, he would return to his dad’s letter to him at 13. What most resonated with him, he says, what he kept coming back to as he was growing older, was the part about choosing the kind of life he wanted to lead. No matter the depth of his knowledge and the vastness of his experience, the older Diokno never imposed his own dreams to his children. “My dad was never one to tell us what to do, [he was never one] to preach. He really led by example,” recalls Atty. Chel.

But he did set a standard his kids might want to measure up to. And he writes it down in closing the 1974 letter to his son. It’s not a recipe for success but for how to be a good, upright, sensitive and strong human being—a wishlist every father would do well to impart to their own children.

“So let me sum up the important things by telling you what is the kind of man I know you can be and I hope you will become: a man who thinks things through and gets things done, quick to admit his mistakes and even quicker to correct them; a man whose eyes are open enough to see reality clearly, and whose stomach is strong enough to take it, but whose heart is knowing and whose head is loving, so that he marvels at beauty but remains sensitive to ugliness; highminded enough to insist upon making his own decisions yet humble enough to seek and listen to advice; a man who savors life but is not intoxicated by success or poisoned by misfortune; who loves to laugh but is not ashamed to cry; who knows his limitations but refuses to accept them as insurmountable…always in possession of himself yet always open to others; in short, a man who kneels neither before men nor before fate, but only before God.

I pray that God give you the grace to become such a man—not always, perhaps, and not perfectly, but at least consistently.

God bless you, son.

Love,

Dad”

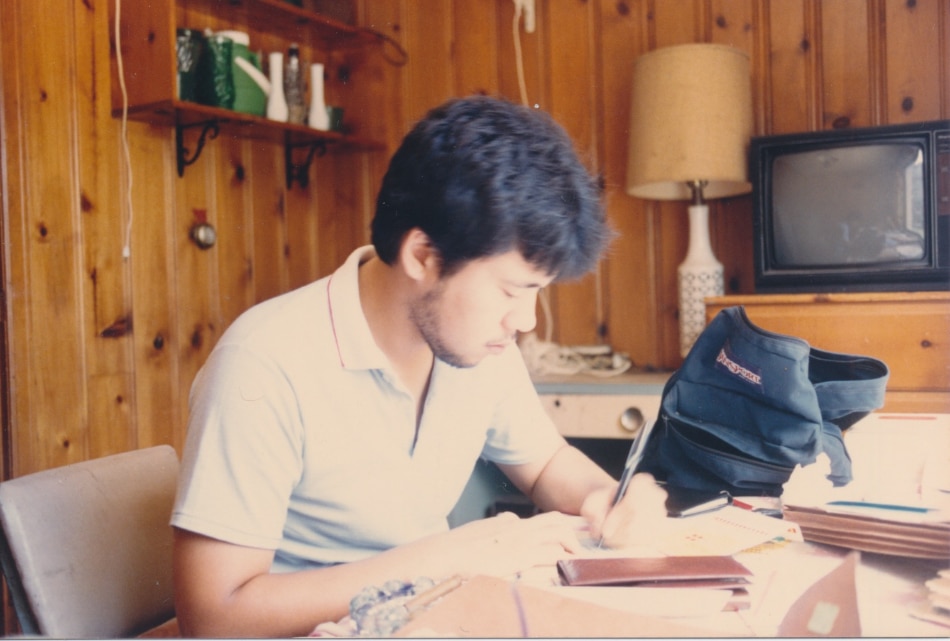

[Images courtesy of the Diokno family]