[As Women’s Month draws to a close, our national hero’s words to the feminists of his day, the ‘young ladies of Malolos’ of legend, still ring true. Seen through the prism of master essayist and wizardess of the historical column, Carmen Guerrero Nakpil, Rizal’s message tells the astounding tale of the Filipino females we should all emulate while throwing a light on Rizal’s own personal experiences with the ‘fairer sex.’

Thanks to more than 10,000 columns, essays and articles, Nakpil was a path-finding proto-feminist. She writes, “Twenty young women who wanted to open a Spanish-language night school in Malolos in 1889 provoked a piece of writing that has become as well-known as Rizal's novel, the Noli, or his last poem, Mi Ultimo Adios. Written in Tagalog by the Philippines' national hero during the crucial period immediately prior to the Philippine Revolution and sent posthaste from Europe in February 1889 — a little more than seven years before the outbreak of the revolution and Rizal's execution — it remains the most authoritative feminist essay in Filipino literature. It is now known as 'The Letter to the Young Women of Malolos.’ But it could very well be renamed — at the end of International Women's Month — A Message to Filipino Feminists.

“As revolutionary rhetoric, the letter shared in the high-minded preachiness of ‘La Solidaridad,’ the fortnightly newspaper of the Filipino expatriates in Barcelona. It throbbed with the anti-clericalism of ‘La Vision de Fray Rodriguez’ and the progressiveness of ‘Por Telefono’, two essays which Rizal wrote during the same period of propagandist ferment.

“But to modern readers, the fervor seems disproportionate to the occasion. Only the surrounding circumstances can explain it.”

An excerpt from Nakpil’s “The Young Ladies of Malolos,” shows us why:]

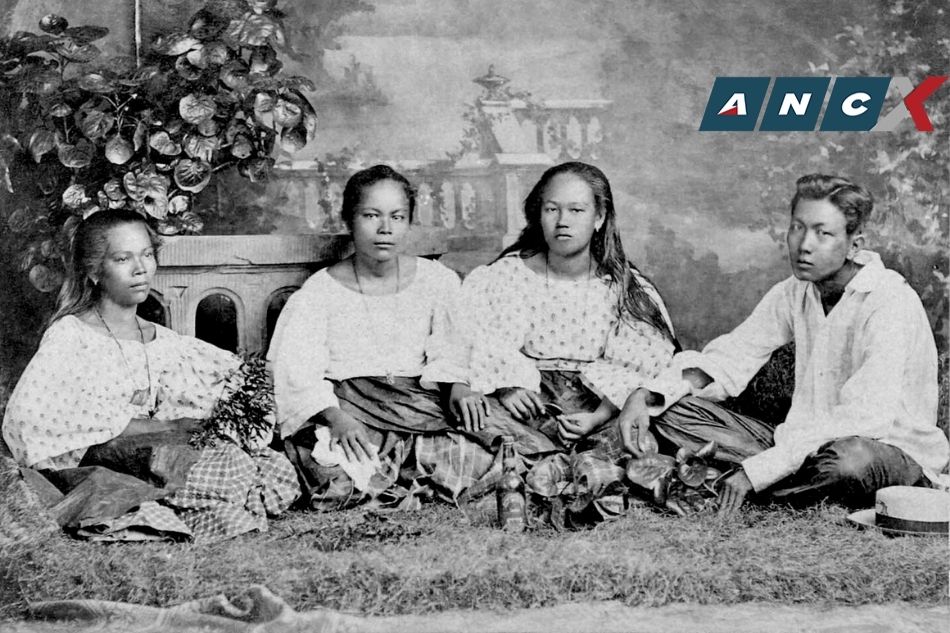

A group of young ladies (the issue of La Solidaridad for Feb. 7, 1889 gives some of their names as Alberta Ui-Tangcoy, Teresa, Maria and Basilia, surnamed Tantoco, and Merced, Agapita, Basilia, Paz, and Feliciana, all surnamed Tiongson) had been trying to secure permission to hire a professor for a private school where they might learn Spanish.

The Spanish parish priest, always on the lookout for subversive activity, frowned on the project and managed to get Governor-General Weyler to disapprove it.

How could Spanish-language lessons — now considered the depths of conservatism — ever have been considered politically dangerous? In the climate of the late 19th century with its peculiar repressive character, that is just what they were.

Sinibaldo de Mas’ gloomy warning against making knowledge available to the native classes was still rumbling in colonial anterooms. Indios who spoke and wrote Spanish were liable to be rebels. As for women who were not confined to convents wanting formal training in the Spanish language — that was unthinkable.

But the young women of Malolos had, with what M.H. Pilar called their 'noble intrepidity' and 'uncommon poise', continued their agitation and submitted a formal petition to the governor during his yearly progress through their province.

They were to meet in the evening in the home of an old familial, chaperoned by their mothers and would pay the professor’s salary out of their own private funds, they wrote in a letter dated Dec. 13, 1888, and some weeks later, permission was granted.

It was just the kind of revolutionary triumph to arouse the admiration of the famous Filipino 'trouble-makers' in Europe.

At the prodding of M. H. del Pilar, the 'chiefest' of them all, Rizal hastily put pen to paper and sent the Maloleñas an emotional, loosely-structured, rambling letter which outlined for their benefit — and, as it turned out, for all of his countrywomen for decades to come — two types of Filipinas, one weak, timid and gullible whom he therefore despised; and another, intelligent, analytical and resolute whom he admired.

Rizal's official biographer notes that there was 'a trace of bitterness in the scorn.' There is little doubt that he was indeed thinking of Leonor Rivera, his Maria Clara, when he wrote that he would have wanted the Filipina to be loved not only because of her beauty and sweetness of character but also because of her strength and loftiness of purpose.

Leonor Rivera who had been afraid of her love for the revolutionary, Jose Rizal, who had chosen the safe path of filial obedience and conformity, was the prototype in his mind, of all those others who were “hoodwinked, helpless and pusillanimous.” Rizal’s pen was dipped in personal gall as he wrote.

“When I wrote the Noli Me Tangere”, he began, “I asked myself if the young women of our people had, as a rule, the quality of courage. Search as I might in memory, recalling those whom I had known from childhood, there were few who appeared to me to come up to my ideal.

“True, there were more than enough with agreeable manners, charming ways and modest bearing but, mixed with all this, due to an excess of goodness, modesty, and perhaps ignorance, were a deference and submission.

“They were like drooping plants, sown and grown in darkness whose flowers were without perfume and whose fruits were juiceless. But now that news of what has happened in your town of Malolos has reached us here, I have realized my mistake and have rejoiced greatly.” Not all the Filipinas were Maria Claras!

The letter then went on to describe (and deride) the habits of 'blind obedience', the cowardice, self-contempt and 'the lack of self-respect,’ the endless prayers, superstitious tales and cardgames to which many Filipinas devoted their days.

Rizal urged his countrywomen instead to assert themselves, to be strong, to develop a 'free mind,' to analyze everything around them and thus 'discover their beginning and their end,' to be firm and fearless.

“What children will that woman have” he asked, “whose goodness of character consists in mumbling prayers and knows only how to recite in chorus awit, novenas and false miracles, whose amusement is gambling .. .'

“What sons will she have but acolytes, servants of the parish priests and cock-fighters? The present state of our countrymen was the work of their mothers, of the boundless naivete of their loving hearts, of the anxiety to win dignities and honors for their sons.

“It is the duty of mothers,” he added to encourage their sons to place their country above their own interests, to “prefer death with honor to life with dishonor.” . .

Filipino women, he said, should emulate the mothers of ancient Sparta who “wielded power over men” because “of all women, they alone gave birth to men.”

If the Filipino woman did not soon decide to exchange her cowardice for strength she faced the possibility of being deprived of her authority in the home and denied the right to educate her children.

For, by her weakness, she might 'unwittingly betray her husband, children, country and all." Did Rizal have a premonition of the day the secrets of the Katipunan would be revealed by a woman to a Spanish friar?

Rizal was even more eloquent on the Filipina as sweetheart and wife: 'Why does not the maiden require from the man she is to love ... a manly heart to be the refuge of her weakness and a lofty spirit incapable of accepting to be the father of slaves? Let her put aside all fear, act nobly and refuse to surrender her youth to the weak and faint-hearted.

“When she is married, she must help her husband, give him courage, share the danger equally with him, cause him no trouble but rather sweeten his sorrows, always bearing in mind that there is no grief which a resolute heart can not bear and there is no inheritance more bitter than that of infamy or slavery.'

It is the wife's duty, he added, to “instill activity, industry, noble behavior and worthy sentiments .. .”

Commending the young ladies of pre-revolutionary Philippines to 'the garden of knowledge' where wisdom was to be judiciously selected from 'unripe fruit' and 'bad seeds' and sampled carefully 'before swallowing,' Rizal signed himself 'your compatriot.

All things considered, the letter remains a tract worthy of a contemporary feminist.

Rizal’s model Filipina — judging from his own description — seems to have been what we would now call a “liberated” woman. His annoyance with women who never questioned authority, who wasted their time on idleness and gaming and superstition, and who, by their demands for comfort security and honors, made cowards of their men, is an outright condemnation of the conventions of femininity.

He urged on his countrywomen the practice of so-called masculine virtues: courage, independence of mind, strength, a thirst for knowledge.

But his mind outreached his emotions. In Dapitan, a few years later, Rizal fell in love and found happiness — not with a woman like Sisa of his Noli, or like Gregoria de Jesus, Bonifacio’s wife and the Lakambini of the Katipunan, who embodied his ideals — but with an Irish girl of dubious origins. “Poor Josephine,” as he called her, half-literate, exploited, pathetic Josephine, who was ashamed of their love and could not summon the mental and moral resources to do justice to his patriotic mission.

“Sweet foreigner, my friend, my joy,” he wrote in his last farewell. But perhaps he was less stern with her because she was not a Filipina.