In a recent webinar hosted by the Philippine Embassy in Spain, Oxford English Dictionary’s (OED) Dr. Danica Salazar stressed the legitimacy of Philippine English. In the same vein as American, British, and Australian English are acceptable variants of the world language, so too is our version says Salazar, who is a world English editor of the revered dictionary that was first published in 1884.

“What OED does is it tells the history of the English language through the development of its words, and that story is not complete if we don’t tell the part that Philippine English plays,” Salazar stresses in the webinar, adding that our variant should not be thought of as wrong—as what hyper-correcting, misguided grammar nazis would have you believe. Philippine English does not deserve all the flippantly derogatory words—such as “carabao English”—it has received over the years, the editor says.

Salazar describes her job in the OED series intended to introduce its editors as mainly involving researching and writing new entries. “But I also look particularly at the dictionary’s coverage of world varieties of English. So [this includes] words that characterize the way that people around the globe use English in their local context.” English speakers outside of traditional centers like the UK and the US, explains the Filipina editor, adapt English words into their everyday life all the time.

For instance, Salazar explains, here in our country many houses have what we call a “dirty kitchen,” a concept that might confound many Brits and Americans. “When we say ‘dirty kitchen,’ it doesn’t exactly mean a kitchen that is dirty. It just means that it’s another kitchen outside of the house where all of the actual cooking is done,” she says. And, for tropical countries like ours where it’s too hot to trap heat and cooking smells indoors, creating a separate kitchen becomes a need—and so is creating a word to describe it.

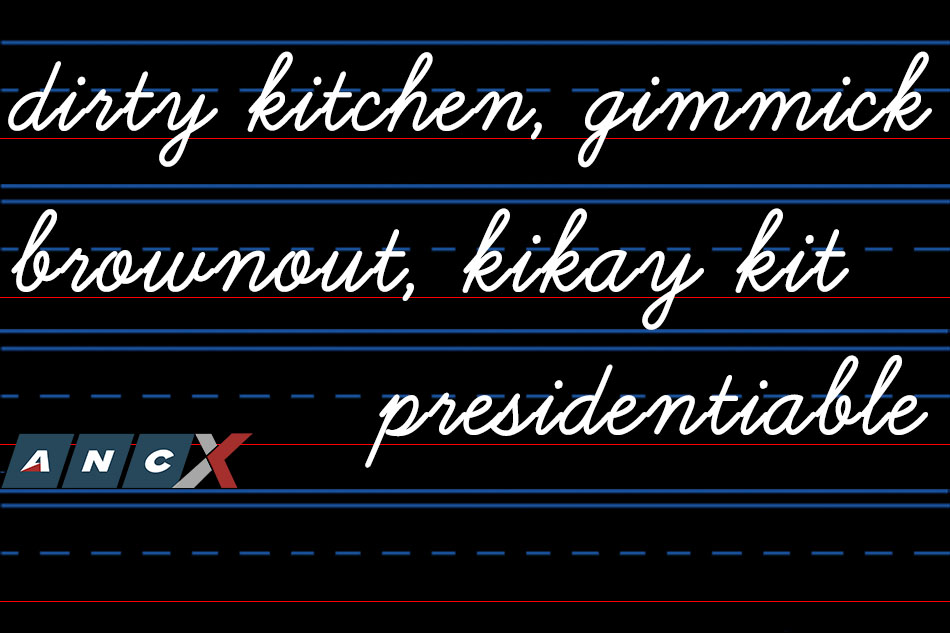

There have been so many of these appropriations, inventions, and localizations of English words into our own variant over the centuries since the language reached our shores in the late 1700s. Think of words and expressions like “brownout,” “comfort room,” “bold,” “high-blood,” and “stolen shot,” which all make use of English words, but find unique definitions and usage in the local context. Many words that the OED has categorized as Philippine English has made it to its pages, starting with “abaca” in 1928. Many more have joined it since then, including “bongga,” “kikay kit,” “adobo,” “gimmick” (to mean a night out), “presidentiable” (to mean a person running for president), and “trapo” (to mean the sort of person that should not be president).

Salazar, whose impressive CV counts doctoral and masteral degrees in linguistics and languages from the University of Barcelona and University of Salamanca, says in the webinar that we must also respect our way of speaking English. Philippine English is rhotic, meaning we pronounce the r at the end of a syllable and before a consonant.

The Philippine accent is one of the most understandable in the world, Salazar emphasizes, and is why our call center industry is particularly successful. She continues that we must not cling to the idea that American or British accents are the correct way of speaking. “The accent and the words that we use, these are a reflection of our identity, of our culture,” she explains, adding that she’s been living in the UK for seven years and no one has complained about her Philippine English accent for not being comprehensible.

In her video introduction, Salazar shares that the OED is now adding more and more of these world English words, which is an endeavor that she loves. “I feel like I learn something new every day, not just about the word themselves, but the language, the history, and the culture of the people who use them. And I feel like every word I work on is like a little window into their everyday realities of English speakers all over the world.”

And, hey, our reality counts, too, as far as the OED and the English language is concerned—so let’s stop thumbing down our noses at our own linguistic evolution. “Adapting languages to suit a communicative means is something that everyone does,” Salazar says. “Americans adapted British English, Australians did the same, people in New Zealand do the same. So why can’t we do the same?”