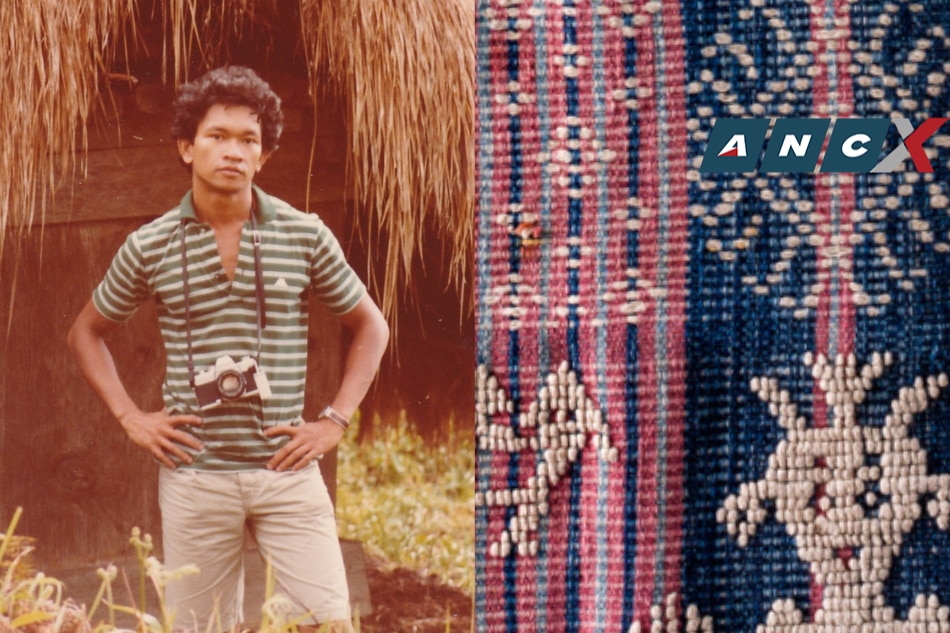

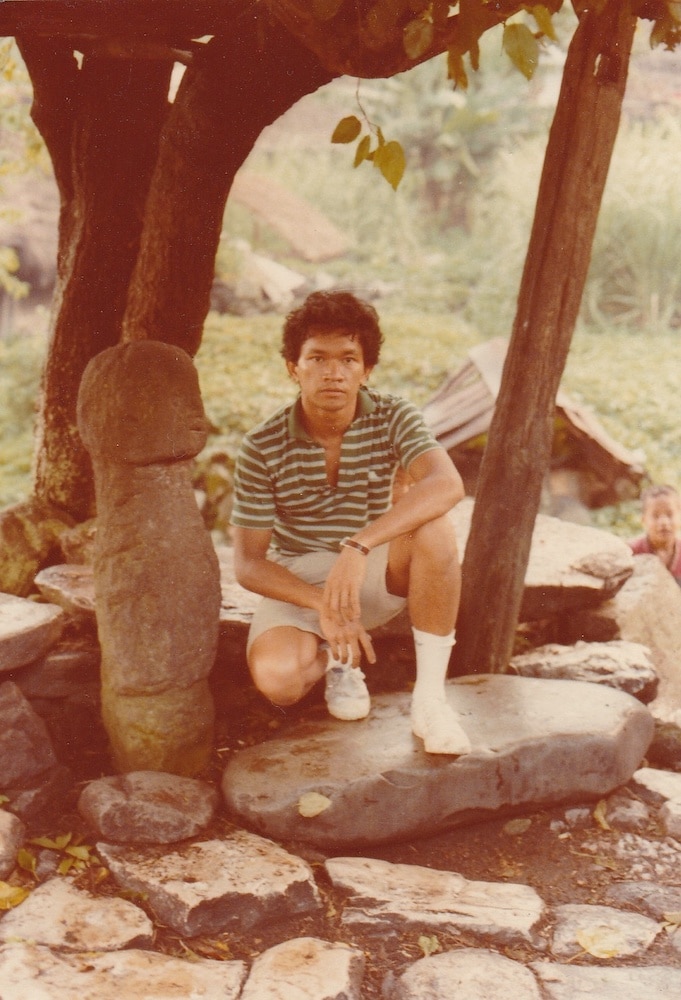

According to playwright and antiquarian Floy Quintos, there are three great early collectors of ancient Cordillera cultural items since the early 1970s, a time when most were collecting Chinese or colonial antiques: Ramon Tapales, anthropologist and collector David Baradas, and Angel Lontok Cruz.

Because he is known to his friends to be gentlemanly and reserved, Cruz is perhaps the least known of the three, but his collection apparently remained to be the most intact until very recently. During the mid-1980s, he and his collection moved to Amsterdam owing to the turbulent political climate in the Philippines. But some of his pieces will come under the gavel this weekend at the Magnificent September Auction at Leon Gallery.

Cruz was one of those who first saw the importance of these indigenous pieces, and yet today, an Ifugao prestige bench, or Hagabi, can go for an easy Php 21,608,000, its hammer price when it was auctioned at the León Gallery last year. Henry Otley Beyer’s son William said it was ‘the king’ of the archaic prestige benches. Now people know the importance of this art from our ancestors.

“What has always lured me to the art and objects of the Ifugao and the Cordilleras, besides some natural affinity,” says Cruz, “is a sense of rediscovering remnants of an original authentic native world, a developed civilization with its own language, social and political hierarchy, a mountain economy, its own system of justice with communal laws and rules, its own religion and rituals, and with a distinct art and even architecture. The objects tell of a time when we were still our original selves, not Hispanized nor Westernized. They remind us in a way of who, as a people, we once were and truly are.”

The Bul’ul

Art, specifically indigenous art, is a reflection of the history, experience and culture of a nation. This is especially true of Philippine art, Filipinos being a visual lot. Hence, one of the most famous symbols of Filipino culture are what people in the Northern Philippines call the bul’ul.

The bul’ul are wooden figures that some groups in the Cordillera, especially the Ifugaos, consider guardians. In some parts of the country, there are similar looking images that some groups call likha or tao-tao. To some, they are representations of the anitos, the spirit of our ancestors, and may even contain their spirit.

According to the book Treasures of the National Museum, rituals are performed by the mumbaki, the local spiritual leader and healer, after the bulul is carved to activate its power or potency (bisa). In these rituals, the story of how the bul’ul came into being is chanted: Once upon a time, the deity Humidhid saw a narra tree wailing and that is why he asked the tree what it wanted to become. The narra tree chose to be a bul’ul. So the tree was cut and carved to become several bul’uls which Humidhid placed in his house. But the bul’uls consumed too much food and wine that Humidhid got so irritated he tossed the figures to the river. They floated downstream.

One of Humidhid’s daughter, Bulan, met one of the bul’uls and fell in love with him, they got married and had kids. When Humidhid met his grandkids, he realized the bul’ul is human and told them that when they come down to earth, they should carve the bul’ul because they will take care of them and ensure their kaginhawahan (well-being).

Bul’uls are usually placed near or inside rice granaries to ensure bountiful harvests. They are venerated so anitos will not inflict illness on the residents, to ensure good health (kagalingan). The bul’uls come in many forms: in fetal position, which is how the dead are positioned, standing up, and male or female.

But I once met a school teacher from Banaue who told me a different perspective about the bul’ul. Their old folks particularly from Barangay Gohang and Uhaj told them that the bul’ul, which they also called tinagtaggu or human figure, were believed to be made during the time of an epidemic in Ifugao, to help the mumbaki cast out the illnesses out of people.

Suffice it to say, there could be many interpretations and beliefs of various peoples on the function of the bul’ul but all denote that it is a powerful image. And the similarities in form represent a common Austronesian heritage which we share with other similar statues in Southeast Asia and the Pacific, including the gigantic Easter Island Moais which look like giant buried bul’uls—a symbol of commonality amidst diversity, hence its appropriation as a national symbol.

We also believe that the appropriation of our culture to Catholicism and its saintly figures is due to the fact that we respected such statues even before colonialism came, denoting the strength of our culture.

More importantly, it tells us of the belief in spirits, the anitos, which were once human beings. It is actually a representation of our very soul which is powerful and have potency (bisa) that leads to wellness (kaginhawahan), a power that comes from mabuting kalooban.

The Grail of Indigneous Textiles

In the auction this Saturday, September 9, a set of two tapestries from Miag-ao, Iloilo from the Angel Lontok Cruz collection, is being dubbed “the grail of indigenous textiles.” The tapestries are made of handspun cotton and organic dye (indigo, and possibly Morinda citrifolia). Floy Quintos quotes scholar, curator, author and museologist, Dr. Analyn Salvador-Amores when he identified the two techniques used in weaving the two pieces: “The supplementary weft technique was used to weave most of the piece. The rarer and harder to execute lower panel employed the single warped face technique, producing an embossed effect similar to the raised Trapunto technique.”

According to Quintos, “The supplementary weft portion is decorated with a motif very similar to (but more crudely rendered than) the eightpoint star motifs common in Itneg pinilian blankets. It is in the lower, single warped face portion where the more intriguing motifs are found.”

“Both borders show a female figure in a farthingale skirt, her arms upraised. She is crowned with some kind of a three-point diadem. In both textiles, this female figure is the central motif. While there are slight variations in the treatment (the marks of individual weavers?), the configuration remains the same.”

Talking about provenance, the two pieces were sold to Cruz by dealer-collector Rolando Go, a man trusted also by Tapales, Barradas, Joaquin Palencia, Ramon Villegas and many visiting French and American dealers. In fact, the Cordillera textiles Cruz sold to Senator Nikki Coseteng in the late 1980s were deemed so outstanding by independent curator and museologist Marian Pastor Roces that she wrote about them in the book Sinaunang Habi, which Coseteng published.

Go mentored the young Floy Quintos. “Oh, he was ever the adventurer, travelling to many places in the Philippines to ‘discover’ (his favorite word) objects and learn about their stories,” said Quintos of Go. “In Iloilo, he was browsing in the shop of Lourdes Dellota (another legend in the field of Philippine antique dealing), when he spotted the first textile. It was then being used as mantle on a table loaded with santos. He asked to see it and was immediately struck by the similarity to Itneg/Tingguian textiles. He was told by Dellota that it wasn’t from Abra in Luzon, but from Miag-ao in Iloilo. Because of the condition, Roland bought it for a song. I remember him telling me that in his excitement, he hired a jeepney to bring him to Miag-ao. There, he walked around the town, blanket in hand, asking random locals what they knew about it. His Eureka moment came when he espied, hanging on a clothesline, a near perfect example which he bought on the spot.

“He was told that these textiles used to be very plentiful, and were produced in Miag-ao (to this day, still a premiere weaving center for hablon). They were not blankets, but tapestries that would be hung from the window sills during fiestas and special occasions. However, he was unable to find anymore.”

Two things should be noted. First point, the two textiles came from Central Philippines but Go noted similarities between the patterns from Itneg or Tingguian from the Ilocos Region of Northern Philippines. Of course, at that time, not so many scholars had emphasized what we now know as our common Austronesian heritage. That despite having many manifestations of cultures in our 7,641 islands, we will see patterns in language, faith systems and material culture because most of us came from our Austronesian-speaking ancestors.

We see the same in the similarities among the many designs of the bul’ul, anito, likha and the Visayas tao-tao; the names of local constellations in ethnoastronomy; the belief in boats that bring you to the after-life and boat-coffins; the reptile patterns that denote common beliefs in fertility and the influence of the Indian naga which we call the divine snake bakunawa, which we also see in the tattoos or batek of the warriors both of the Cordillera and the Visayans (as exemplified in the 16th century illustrations in the Boxer Codex) and also the Irranun and Balanguingui groups in Mindanao, which transform them as snake people, which brings us to Apo Whang-Od of the Butbut ethnic group in Kalinga, Northern Philippines, supposedly the last tattoo artist to be able to place them in warriors. Because every battle won was commemorated by a tattoo, and that is why up until today a skilled person is called a “batikan,” a man with many tattoos.

The technique was passed from one generation to another, which doesn’t mean it will not undergo changes. The Spaniards came to colonize us and now bring us to my second point. Scholars believe the two pieces came from the late 19th century therefore shows us some elements of Catholic imagery as brought about by the Spaniards. As pointed out by Quintos: “The design repertoire in both panels also include: (1) An unidentified animal with a paw upraised, possibly a reference to the symbol of the Lion Rampant from the Spanish seal. (2) An abstracted reference to the Hapsburg double headed eagle, also the emblem of the Augustinian order, of whom the Hapsburgs were patrons. (3) A smaller quadruped animal (dog?). (4) A frieze of upright and inverted triangles. It is worth noting that all the motifs found in the Miagao examples also exist in the Itneg textile repertoire. A recently discovered Itneg blanket in a private collection shows these designs covering the entire field of the textile.”

Quintos continues, “These are therefore extremely rare weaving which deserves the concentrated attention of scholars.” Marian Pastor Roces says: “These two pieces are of singular importance. Because of the questions they pose, and the possibilities of further study and scholarship that they open, these textiles are clearly treasures of national importance."

Many times, in our nationalist discourse, it is said the colonizers erased our culture and replaced it with theirs. For me, all these indigenous pieces are important because they are a tangible reminder of the strength of the Filipino culture, which was able to appropriate the elements of the foreign and made it our own—and which survives to this day.

Hence, all these items, the bul’uls and these “grails” of indigenous textiles, are reflections of our common national experience, all its pain and beauty, not written in words and details by historians, but in meaning and imagination by our local dream weavers. A perspective from the people themselves. Isang kasaysayang mula sa bayan.

The Magnificent September Auction is happening this September 9, 2023, 2 PM, at Eurovilla 1, Rufino corner Legazpi Streets, Legazpi Village, Makati City. Preview week is from September 2 to 8, 2023, from 9 AM to 7 PM. For further inquiries, email info@leon-gallery.com or contact +632 8856-27-81. To browse the catalog, visit www.leon-gallery.com. Follow León Gallery on their social media pages for timely updates: Facebook - www.facebook.com/leongallerymakati and Instagram @leongallerymakati.

All photos courtesy of Leon Gallery