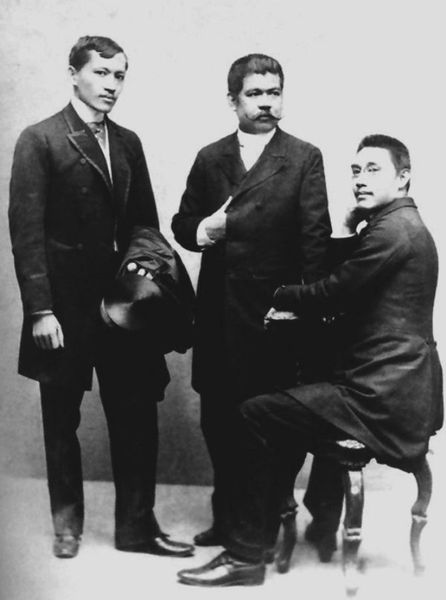

In the middle of the night in 1861, a tisoy baby boy was born to Doña Teodora Alonso and Don Francisco Mercado in Calamba, Laguna. No one thought the baby would grow up to be a well-travelled doctor, artist, writer, historian, poet, master-fencer and, eventually, a national hero.

José Rizal was born in one of Spain’s last remaining colonies plagued by frequent rebellions and insurrections. At the same time, the Philippines was faced with an unsure future, no thanks to the prevailing backward and oppressive rule of the Religious Orders, and a civil government entangled in the battle between Liberalism and Conservatism. In 1872, a bloody mutiny in Cavite took place, which led to the eventual execution of three secular Filipino priests. This, according to Patricio Abinales and Donna Amoroso’s book State and Societies in the Philippines, rocked the entire country and sent shivers down the Liberals’ spines. All seemed bleak for Spain’s far-off tropical colony. But that mestizo baby’s birth would help change the course of the country.

You may also like:

- All the girls Rizal loved before

- VIDEO: A tour of Rizal's Madrid, from his favorite bar to the La Solidaridad headquarters

- First wives, last rites, and the last book Jose Rizal ever read

- As we celebrate Rizal's birth, we remember his mother and her heartbreaking life

- How the “Noli Me Tangere” was our first content to go viral

- 9 Rizalian examples for today's Filipinos

- What Rizal taught us about the pitfalls of spreading and reading fake news

When the young José Rizal entered Ateneo Municipal in the cuidad murada, Intramuros, it was obvious he was to have his first interactions with Europe and her sons. Run by Spanish Jesuits, Ateneo offered subjects that let gifted Spaniards and Filipinos explore the world of Virgil and Cicero, learn the language and stories of Caesar, Don Quixote, and Oedipus and discover other subjects that were European in taste and orientation. To say that Rizal did not learn Spanish, Latin, French, and Greek in Europe is true; he was still a young man here in the Philippines when he started reading, writing and speaking in these European languages.

To his great benefit, the access to these languages was also a means for the young Rizal to be exposed to Ateneo’s immense wealth of books and lessons. But Rizal’s early interaction with Europe was not only through Spain’s books and institutions. It was also through the continent’s sons—his Jesuit Fathers and Brothers. With the erudition, guidance, and paternal care these Jesuits showed young José, the future propagandist of the Philippines saw in these men the love and concern of Mother Spain he had always hoped for. These priests were, for him, shining beacons of what Europe then could best offer: an intelligent and rational but God-centered outlook in life. For these men to come to the Philippines and teach young boys like him Mathematics, Rhetoric, History, Geography, Latin, Spanish, French, Greek and more, an indelible mark was impressed upon the young José. Europe was a haven, a source of great ideas and, more importantly, a place for enlightened and compassionate men.

But José was still in the Philippines and his larger reality was different. Although his family already belonged to the principalia class, Rizal and his loved ones were subject to the humiliation and dispossessions that Filipinos then had to endure, as León Maria Guerrero relayed in his book, The First Filipino. History tomes and Rizal biographies would mention how the young Rizal witnessed his own mother get a taste of the wickedness of the colonial system, being wrongly accused and incarcerated for around two years. As recorded in Abinales and Amoroso’s book, State and Society, in the late 1800s, religious corporations led by peninsular priests were also habitually raising the rents of their huge haciendas, making the inquilinos as well as the kasamas feel the economic brunt.

Beyond school

How then could one see the role of Europe in the Philippines? What does this continent have to do with the plight of all the indios, sangleys, mestizo sangleys and criollos in these islands?

The short answer? José Rizal. It is in his heart and mind that a union of European ideas and cultures found and will find meaning. Life in a primary school like Ateneo was not enough for Rizal to access and comprehend the numerous ideas and cultures spread throughout Europe—lest it be forgotten that Ateneo Municipal was still a Catholic and Spanish institution cautious of what materials its students may read.

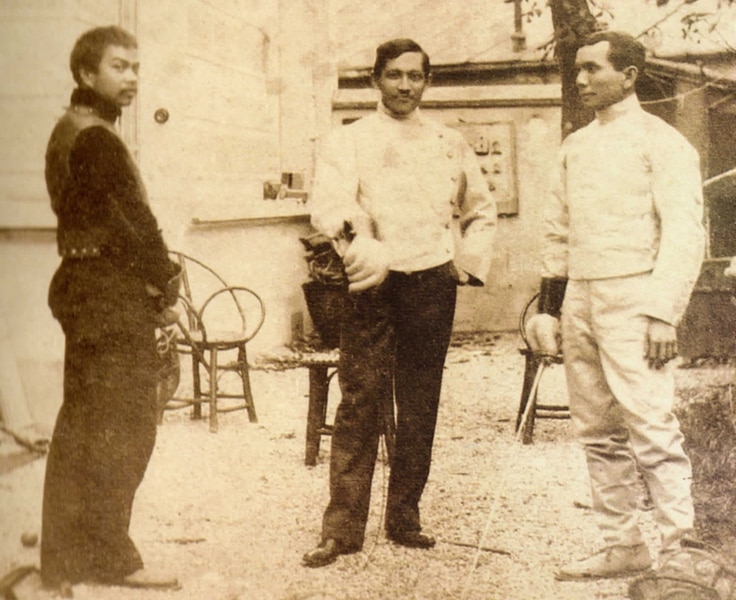

Fortunately, his eventual stay in Europe for further study opened and broadened his mind, seeing European countries as examples his own country should try to emulate. It is not an exaggeration to say that Rizal might have felt jealous of the Europeans who were able to freely discover the wonders of science and mention words such as “reason” and “progress” without being flogged by the local parish priest. As he set foot in the great continent, he indulged in some academic and not-so academic pursuits, a young man so thirsty of knowledge. He joined the Circulo Hispano Filipino, wrote his masterpieces Noli Me Tangere, and El Filibusterismo, and forged long-lasting friendships with some European men and women. While there, he was elected member of the Geographical Society as well as the Anthropological Society, and other scholarly groups. Europe expanded his world view.

The great European countries of Spain, France, Germany, England, Belgium, and Italy have left indelible marks in Rizal’s life. To simply paint a picture of his frolicking through the continent and burning his family’s money is misleading and irresponsible. As he went from one country to another, he had a purpose for each transfer. For one, having very little money. he was looking for the cheapest printing press which could publish his controversial Noli. Secondly, travelling through Europe enabled him to learn new and useful languages and one of these is German. His facility in the language enabled him to read more scholarly materials and forge new relationships. Germany also left a deep impression in him, and he would always recount examples of German loyalty and honesty.

Among Rizal’s new acquaintances in Europe, a Czech stands out as his favorite: Ferdinand Blumentritt. A school master from Leitzmeritz, Blumentritt’s somewhat peculiar interest for the Philippines caught the attention of Rizal because it brought him hope and encouragement. Indeed, beyond the Iberian Peninsula, there were other Europeans, other people out there, who knew something about the Philippines. It so impressed Rizal that a Czech was very interested and adept in Philippine History. The emotional and sensitive Rizal was utterly touched the moment he heard in Heidelberg that “a professor Blumentritt was studying Tagalog and had already published some works on the language.”

Rizal had every reason to find in this man an advocate, confidante and friend. From exchanging letters, the relationship grew into a lasting friendship and, even to some extent, brotherly love. Blumentritt was Rizal’s virtual elder brother and mentor, a companion through the hard and expensive life in Europe. Rizal would also extend a helping hand to Blumentritt by translating manuscripts, and at the same time, opening Blumetritt’s eyes to a Philippines beyond ethnographies, maps and dialects. It was in this friendship that Europe found a place in José Rizal’s heart.

Their friendship was proof that being one’s best can lead the other to love and appreciate the other’s homeland. For the Rizal, Blumentritt was what Europe best offered him.

After his first and last meeting with Blumentritt, Rizal was set to leave Europe for Calamba. His stay in that continent was no bed of roses; the cost of living was high and his own family, being in turmoil over land disputes, had difficulty sending him money. Rizal was not only in Europe to write letters to foreign friends and attend parties; he was there to study and, eventually, campaign for reforms. His stay exposed him to different cultures and practices, good and bad. And through these he was also able to formulate ideas as to what reforms are needed in his home country, among them having a free press.

Rizal and his convictions were a product of his European experience. Readers of history should see that along with Rizal’s return to the Philippines was the arrival of his European-inspired thoughts. From her shores, the First Filipino will return to his country renewed with vigor, strengthened by the French ideas of liberte, fraternite and egalite, hopeful that his sojourn in Europe made him a better Filipino. Influenced by the French Revolution’s ideas, impressed by German ingenuity, Rizal was so hopeful that one day the Philippines would be considered one of Spain’s provinces. Europe was in his heart, but his heart was still for the Philippines.

Works Cited

Guerrero, León Ma., The First Filipino. Philippines: Guerrero Publishing, 1998.

Abinales, Patricio, and Donna Amoroso. State and Society in the Philippines. 2005.

Pasig: Anvil Publishing, 2007.

*This essay was awarded the grand prize in the “Rizal na, Europa Pa” nationwide essay writing contest, organized by the European Union delegation to the Philippines, the different EU Cultural Institutes (including Instituto Cervantes de Manila, Alliance Française de Manille, Goethe Institut, among others) and the Order of the Knights of Rizal. It was recognized in ceremonies last June 18, 2009 at the Music Hall of Mall of Asia. The grand prize was a trip through Europe, revisiting important sites associated with Dr. Jose Rizal, starting with the city of Paris.