“Hello. My name is Woldy. I am a chef, and I am deaf.” That’s how Woldy Reyes, the man behind one of New York's sought after catering services Woldy Kusina, greeted his Instagram followers recently, while also translating his message in sign language. It’s his contribution to Deaf Awareness Month which takes place every September.

Being deaf was something Woldy was ashamed of when he was younger, because it made him feel inadequate, less of a person than the next kid. Over the years, however, he learned a lesson that will change his life and how he viewed the world around him: He needed to “love all the things that I am.” He will no longer let deafness prevent him from doing what his heart desires, which is cooking and connecting with people.

Woldy’s journey is a pretty unique and inspiring one. Not only did he have to navigate the New York fashion and food scene as a deaf person, he also had to find his own place in that very competitive universe as a Filipino-American and queer person.

The Los Angeles-born Woldy has come a long way from his fashion assistant days at Elle and Nylon magazines. His Woldy Kusina is now considered one of the Big Apple’s top catering businesses, having served a clientele that includes American fashion brand 3.1 Phillip Lim, the home furnishing retailer West Elm, and cosmetics brand Kosas. He’s also been featured on the New York Times and Gwyneth Paltrow’s goop.

Getting to where he is now was not without its share of hardships and challenges.

Two of a kind

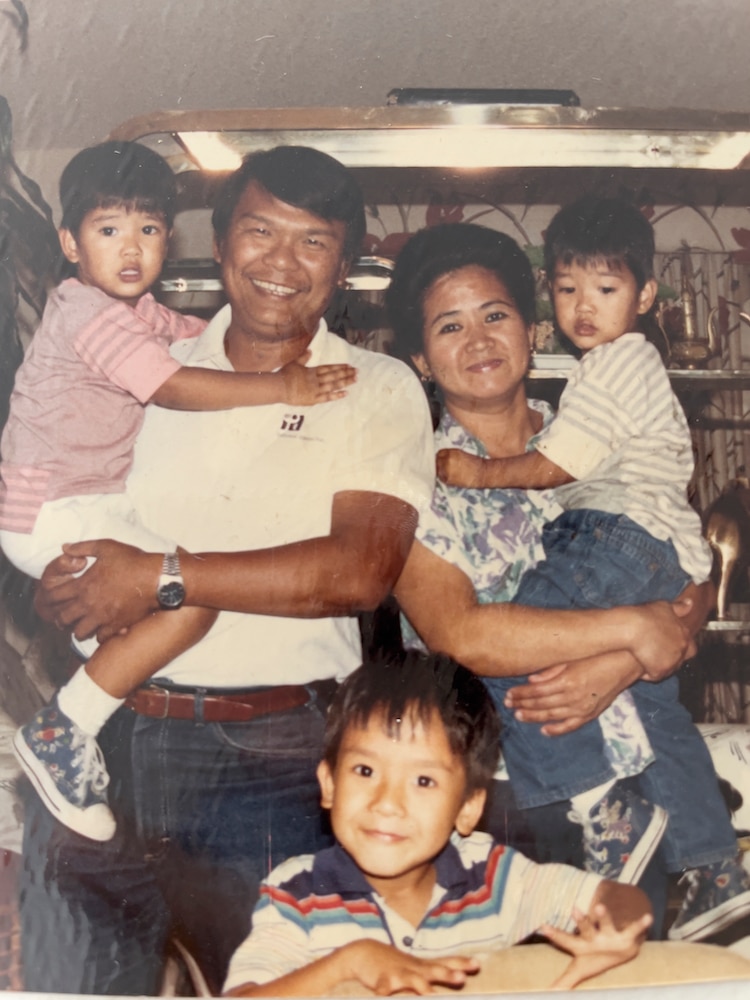

Woldy was about four or five when his parents, Wilfredo and Emma, both from the Philippines, discovered their twins were deaf. “[My brother and I] both have hearing loss. Wally has more of a profound hearing loss than mine,” Woldy tells ANCX from his pad in New York. “I can hear partially and I was able to talk; my twin brother wasn't able to talk at that time.”

Growing up, Woldy had to wear a hearing aid so that sounds around him are louder and clearer, and so he can fully understand what was going on in his immediate surroundings. At some point, while growing up, the twins had a sign language interpreter going with them to school. The Reyes boys also had to go thru speech therapy. Eventually, the family decided to study sign language together—so they can communicate better with each other.

“At that time, I didn’t quite understand [the situation],” he recalls. “There were certain things that my parents didn't allow us to do, like sports, because they weren't sure how it's going to affect us. But I also knew they were doing everything that they could with the information that they had, to help us.”

Despite all the efforts, Woldy still found it difficult to fit in school. His condition was considered a disability. “At that time, the word disabled can mean different things,” he says. “Then also being queer and being a Filipino American—all of these things that I am, it was a lot to navigate and I just wanted to be invisible.”

It was when he entered college at The Collins School of Hospitality Management in California when he began to really accept being queer and deaf. In an interview with medium.com, Woldy shared that meeting others who are also different, and coming out to a friend and coworker, liberated him.

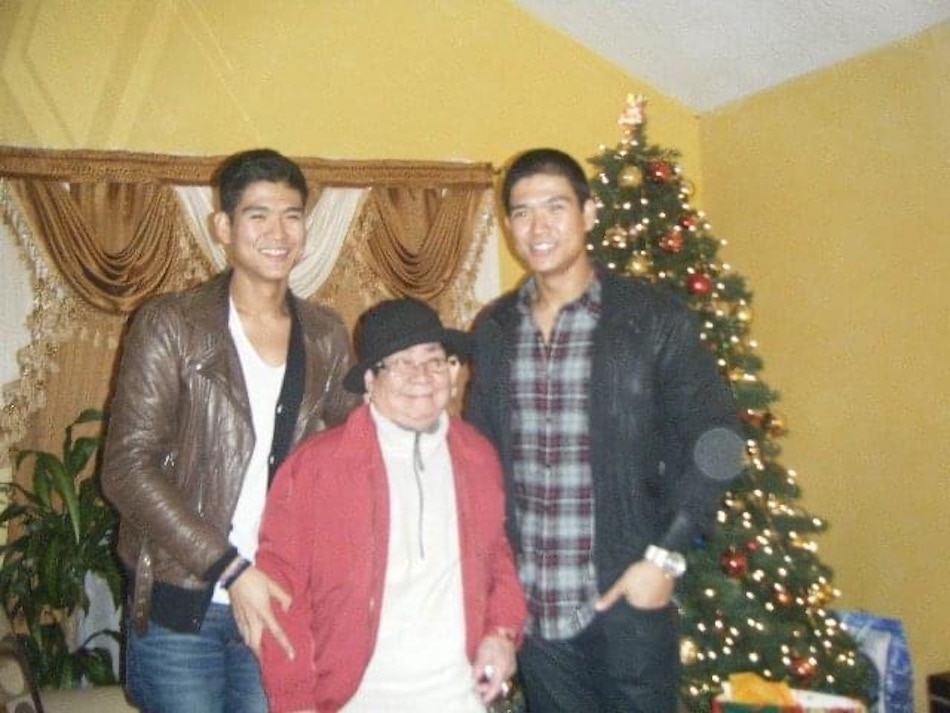

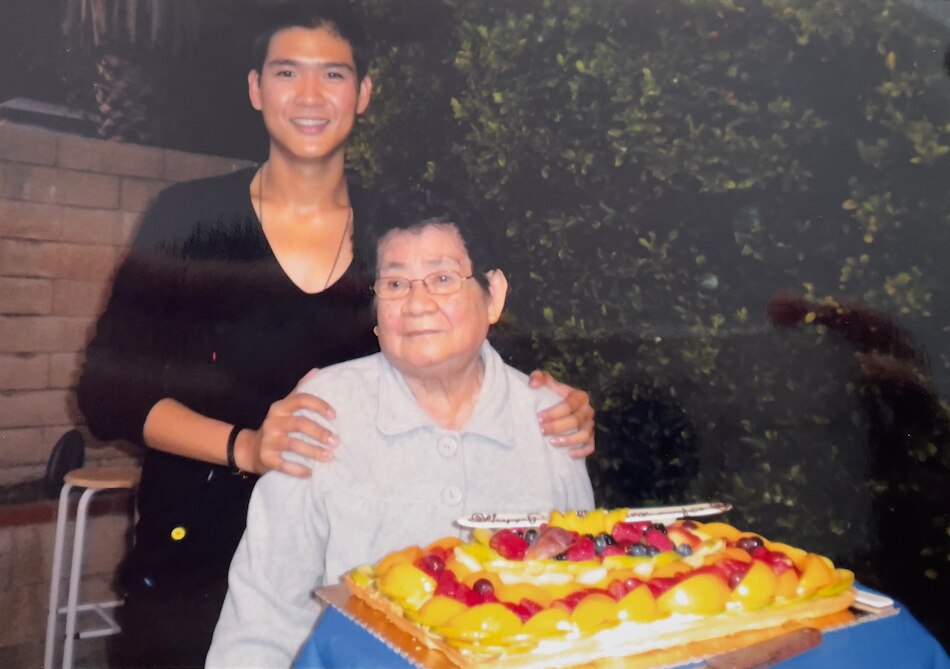

He's also thankful to his maternal grandmother Dominga for accepting him for who he is. “I felt more connected to my Lola just because I think she sensed that I was different. She held me close to her. Just thinking about her makes me very emotional,” Woldy says, trying to hold back tears. His Lola, who he fondly calls Lolly, passed away two years ago.

At Collins, Woldy majored in hotel and restaurant management. But he did not immediately pursue the field professionally after graduation. He decided instead to move to New York City and explore his other interest—fashion. His work at Elle and Nylon magazines was followed by a job at the sales and visual merchandising department of 3.1 Phillip Lim. He worked in fashion for a total of six years before switching to food and cooking.

Fashionable food

It was in 2016 when Woldy decided to get serious in the culinary field. “When I first started, I didn't want to call myself a chef, just because I didn't go to culinary school,” he says. “When people asked which culinary school I went to, I'd say, ‘I learned from my Lola.” His lola, says Woldy, was a “vibrant, intelligent, loving woman.” She was like his second mother.

Woldy got his early exposure to cooking from his father, who passed away when Woldy was 14, and from his mother Emma. “Growing up, I was fortunate enough to enjoy all these incredible dishes like adobo and sinigang that my family cooked,” he says. “What I do now is try to interpret and modernize the dishes in the way that I would want to eat them today and share them with people here in New York.”

Woldy’s mushroom adobo, for example, for Woldy Kusina was inspired by his Lola’s adobo. “It's a coconut milk-based adobo that has tamari (a variety of rich, naturally fermented soy sauce), vinegar, black pepper, and garlic. Being mindful of my clients’ dietary restrictions, I use mushroom in lieu of the pork or chicken,” he offers. He serves the dish with jasmine rice and tops it with vegetable slaw.

Then there’s Woldy’s version of pancit which uses sweet potato noodles brought to life with an array of rainbow fresh vegetables: cabbage, bell peppers and carrots among them. Holding these ingredients together is a delicious dressing that consists of tamari and sweet chili sauce. “I make pancit but I turn it into more like a noodle salad,” says the chef.

He also has an homage to our chicharon bulaklak but it’s a plant-based take, made less indulgent with the use of mushrooms. He also coats the oyster mushrooms with rice flour and coconut milk before deep frying them.

Asked how he comes up with the ideas for his dishes, Woldy says he simply refers back to what he enjoyed eating with his family growing up—while thinking of ways to interpret them into something more contemporary. While not a full vegan, the 36-year-old Fil-Am says he wants to be more intentional about the food he makes and consumes and consider their effect on the body and on the planet. “Many people are making steps towards being mindful. And so I'm making a conscious effort to help shape or change the way people eat, and also allow them to learn about a culture that they'd never experienced before,” he says.

Woldy says his exposure to the world of fashion definitely influenced how he approaches cooking. “It's about using colors, texture, and telling a story visually,” he says. “I enjoy the process of styling food, and luckily, the fashion community understands how important visuals are in the overall dining experience—you eat the food with your eyes first!”

Just like dressing up, cooking is a form of expression for Woldy. He presents his food the way he wants to connect with people. “It's literally telling a story. That's how I express my creativity.”

Cooking as a safe space

It’s not easy being a chef who’s partially deaf. “I had to really go above and beyond [what others do] and show people what I'm capable of. I still do that till today because I feel like I have to prove something all the time to feel validated, to feel worthy,” Woldy admits.

He says he also makes sure people are aware of his condition. “I have to let people know that I might not hear them the first time they speak up, and they have to speak a bit clearer,” he says. Sometimes he feels people get frustrated when he constantly asks them to repeat what they said. “At times, they simply shrug if off and I think that's not fair to me because I'm trying to understand what they are saying. It makes me feel isolated.”

Woldy admits it's hard not to be emotional thinking about what he’s gone thru. But he’s also not the type to dwell on negativity.

Cooking, especially professionally, helped a lot in building his confidence. It became his safe space. “As I cook more and share more, I continue to love myself more and I found my purpose—meaning that I'm able to nourish people. I am able to show my creativity through food and it excites people.”

“When I show myself on a plate and it's beautiful, it's complex, it's layered—people love it and it gives them hope. Hopefully, I’m able to connect with people not only through their bellies but also through their hearts.”

To mark Deaf Awareness Month, Woldy has a message for his followers: learn sign language, support deaf-owned businesses, and share the stories of deaf believers. But he also has a message to those suffering from hearing loss. “You are worthy and you can do it. Don't let your disability hold you back. It actually makes you even more special,” the chef advises. “I might not be able to hear fully or naturally, but I can tap into my other senses and that's worth celebrating. Your disability is not something that will prevent you from doing things. It actually just even makes you more able.”

Photos from Chef Woldy Reyes